TL;DR — What You Actually Need to Know

Purpose: Learn how to tell Bell’s palsy from stroke.

Do this first: Look at the forehead and do a quick neuro screen.

Red flags: Speech changes, limb weakness, gait issues, severe headache, vision changes, altered mental status.

Initial tests: Glucose, full neuro exam, stroke pathway if anything feels “off.”

First-line treatment for Bell’s palsy: Steroids within 72 hours, consider antivirals, protect their eye

Follow-up: Recheck in 48–72 hours. Stroke symptoms → immediate EMS transport.

At-a-Glance Comparison Table

| Feature | Bell’s Palsy | Stroke |

| Forehead involvement | Yes (can’t raise eyebrow) | No (forehead spared) |

| Onset | Hours | Seconds–minutes |

| Other neuro deficits | Usually none | Often present |

| Speech changes | No | Common |

| Limb weakness | No | Yes |

| Eye closure | Weak on affected side | Normal |

| Pain behind ear | Sometimes | Rare |

| Red flags | None typically | Many |

| Imaging | Not routinely needed | Required if stroke suspected |

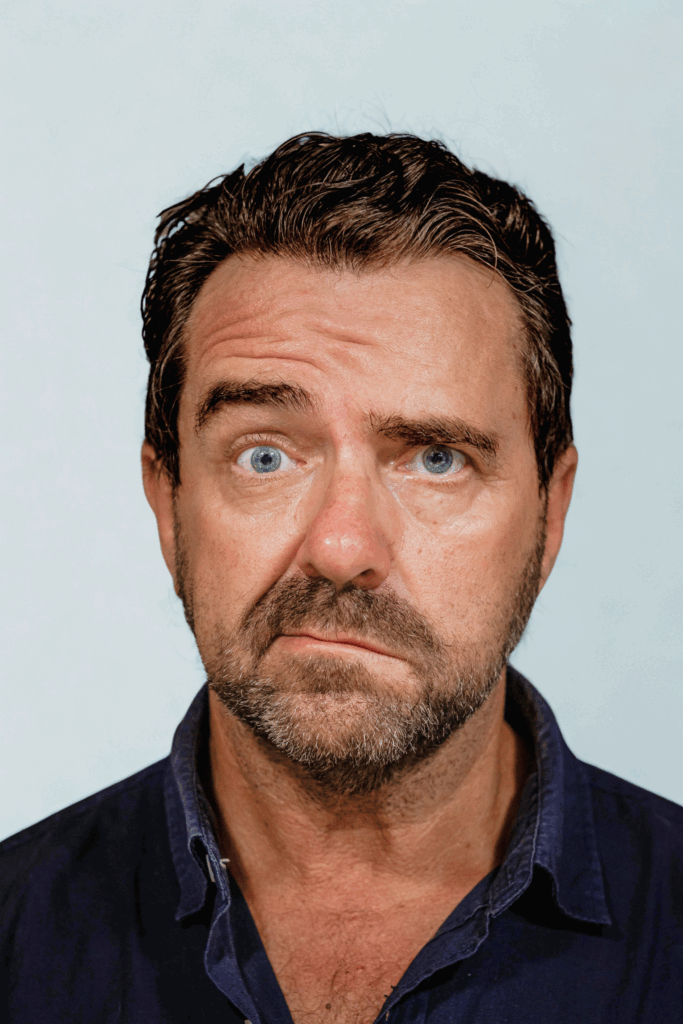

When to Suspect Bell’s Palsy

Bell’s palsy is a temporary paralysis of the facial nerve on one side, usually secondary to a viral infection (most commonly, HSV). The lower AND upper face is affected, including the forehead.

Think Bell’s palsy when you see:

- full unilateral facial weakness

- forehead involvement (can’t wrinkle it)

- trouble closing one eye

- normal speech, gait, and extremity strength

- onset over a few hours/days, not instantly

Patients often report their:

- Taste is “off”

- Eye feels “weird”

- Face feels “tight”

When to Suspect Stroke

Any other focal neurological deficits should make you think of a more serious underlying issue:

- forehead is not involved

- onset is sudden or witnessed

- slurred speech

- unilateral arm or leg weakness

- sensory changes

- gait difficulty

- vision loss or double vision

- severe or unusual headache

- altered mental status

- they just “look off” (listen your gut!!)

If their presentation or your exam is even slightly concerning, activate your facility’s stroke protocol and transport via EMS.

The Exam: What to Actually Do

Here is a thorough but quick cranial nerve exam (start at 0:25). And another, more comprehensive neuro exam that I like (start at 0:54).

1. Look at their forehead

- Stroke = Patient can raise their eyebrows

- Bell’s palsy = Patient can’t raise eyebrows.

2. Ask them to close both eyes tight

- Stroke = eyes close normally

- Bell’s palsy = one eye won’t close fully

3. Smile test

- Stroke = lower face droops but forehead spared

- Bell’s palsy = whole side droops

4. Speech

- Stroke = slurred, slow, or “off”

- Bell’s palsy = normal

5. Extremities + Gait

Do not skip this. Make your patient move around, get up and walk, and interact with you. If they can’t walk normally, it’s a stroke until proven otherwise.

Decision Rules

If ANY of these are present:

- new speech changes

- limb weakness

- altered mental status

- sudden severe headache

- vision loss

- inability to ambulate normally

- forehead not involved

Treat it like a stroke.

Bell’s Palsy Treatment Plan

1. Steroids

Start within 72 hours. This is the timeframe when steroids can improve outcomes.

A common regimen is Prednisone 60 mg daily for 5 days, then taper (OR use a simple 7-day burst if your site prefers).

2. Antivirals

Consider adding an antiviral to glucocorticoid therapy, especially if patient has severe symptoms. Common regimens include Valacyclovir 1000 mg three times daily for 7 days

or Acyclovir 400 mg five times daily.

3. Eye protection

For some patients, the inability to fully close the eye puts them at risk for corneal injury. Don’t skip this step! Recommend:

- Artificial tears during the day

- Lubricating ointment at night

- Tape eyelid closed for sleep

- Ophthalmology if corneal injury suspected

4. Pain management

- Warm compresses

- NSAIDs

- Reassurance

5. Follow-up

Re-evaluate 48–72 hours if symptoms worsen or you’re uncertain.

Consider neuro referral for any patient who is:

- worsening after 1 week

- has recurrent episodes

- has atypical features (bilateral, slow progression, vesicles, systemic symptoms)

Stroke Treatment

This part is actually pretty simple from the outpatient perspective:

- Call EMS / activate stroke protocol

- Check glucose

- Document last known well

- Do FAST exam

- Do not delay transport for labs, CT, or your own curiosity

Differential Checklist (Just in Case)

- Ramsay Hunt Syndrome (check for vesicles in ear)

- Lyme disease (geography, rash, tick exposure)

- Otitis media/mastoiditis

- Brainstem stroke (rare but possible)

- Tumor or mass (gradual progression)

- Guillain Barré (bilateral weakness)

FAQ

1. Does Bell’s palsy ever spare the forehead?

For all intents and purposes, no. If the forehead works normally, you need to rule out stroke.

2. Should I order imaging for Bell’s palsy?

Not routinely, unless symptoms are atypical or red flags are present.

3. Should every Bell’s palsy patient get antivirals?

Not mandatory, but reasonable for severe or rapidly progressive symptoms. Strongly consider prescribing for those with House-Brackmann scores of IV/4 or higher.

4. How long until Bell’s palsy gets better?

Most patients improve within 3 weeks and recover fully within 3 months.

5. How do I know if it’s from Lyme disease?

Lyme can cause a peripheral facial nerve palsy that looks exactly like Bell’s palsy, so it should always be on your radar in the right geography or season.

Think Lyme if you see:

- new unilateral facial weakness

- history of hiking, camping, or outdoor exposure

- known tick bite (but half the time they don’t remember one)

- recent viral-like symptoms

- rash, especially anything suspicious for erythema migrans

- symptoms in late spring through early fall

What to do:

- Test for Lyme if clinically appropriate

- Treat Bell’s palsy normally with steroids

- If Lyme is confirmed or strongly suspected → treat the Lyme (doxycycline is first-line in adults)

Patients who present with facial droop can feel really intimidating, especially as a new provider. It gets easier when you know what to look for. If this kind of “tell me what actually matters” approach is your style, Blox was built for you.